The treatment of disease through precision medicine requires novel research not only at the molecular level, but also on human, animal, and plant cells. Six expert chemists, linked by a shared mission, presented their latest findings to faculty and students at the inaugural Yale Chemical Biology and Organic Synthesis Symposium on May 13 and 14.

The event merged two long-standing symposia at Yale Chemistry. Reflecting ever-expanding interdisciplinarity, the new program builds on the proud traditions of the venerable Yale Chemical Biology Symposium and the Connecticut Organic Symposium. In welcoming remarks, Professor Seth Herzon, Ph.D., Milton Harris ‘29 Ph.D. Professor of Chemistry at Yale, stated, “many of us share the same research interests, and our work frequently overlaps. It made sense to finally combine these two symposia that date back 20 years at Yale.”

“It is always challenging to try a new model following a great run, as we had with the Yale Chemical Biology Symposium and the Connecticut Organic Symposium. But this really worked and brought people together. I am already very psyched for the next installment in the year ahead.”

- Scott Miller, Ph.D., Irenee du Pont Professor of Chemistry, Yale University

Guest speakers explored the role of diverse molecules on topics including plant and disease-associated biology, transformative medicines for treating diseases, synthetic organic chemistry, and catalytic processes.

The first speaker, Véronique Gouverneur, Ph.D., professor in chemistry at the University of Oxford, presented her work on fluorine chemistry that aims to develop synthetic methodologies that prepare fluorinated targets. Her research on creative fluorination reactions culminates in applications in medicine.

Another synthetic chemist, Kami L. Hull, Ph.D., associate professor in chemistry at the University of Texas at Austin, demonstrated how transition metal-catalyzed amination reactions reduce the time and waste associated with synthetic organic chemistry. This work facilitates the efficient synthesis of biologically active compounds.

Paul J. Hergenrother, Ph.D., Endowed Chair in Natural Products Chemistry and professor of chemistry at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, illustrated how his laboratory uses small molecules to leverage protein overexpression to identify novel treatments for cancer and drug-resistant bacteria.

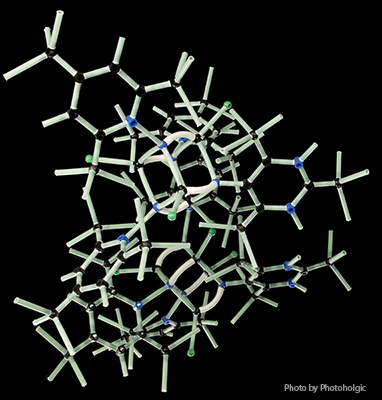

On a similar quest, Matthew D. Disney, Ph.D., professor in chemistry at The Scripps Research Institute, outlined his findings on the sequence-based design of small molecules targeting RNA structures, which play a role in all diseases. His research group develops rational approaches to design patient-specific therapies for diseases like muscular dystrophy, Alzheimer’s, ALS, infectious diseases, and difficult-to-treat cancers.

The inspiration of Elizabeth Sattely, Ph.D.’s work is the intersection of human reliance on plants and plant-derived molecules for food and medicine. Sattely, an associate professor of chemical engineering, Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigator, and fellow at Stanford University, examines chemistry from plants, noting their position as the source of 10% of essential medicines. She discovers and engineers plant metabolic pathways to make molecules that enhance human and plant health. One such example is the creation of a natural chemical ‘vaccine’ to protect tomato plants from lethal infections, which could save entire harvests.

Stephen L. Buchwald, Ph.D., Camille Dreyfus Professor of Chemistry at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, gave the final talk of the symposium on palladium-catalyzed carbon-heteroatom bond-forming reactions.

Buchwald, who has won many awards, including the prestigious Wolf Prize in Chemistry, humbly imparted a history of his grant writing trials and tribulations, offering students lessons learned along the way. He concluded the symposium with this career advice: “Don’t be afraid to get into things that you don’t know all the answers to, collaborate with the right people, talk, admit when you’re wrong – particularly when your students tell you that you’re wrong – and try to enjoy it.”